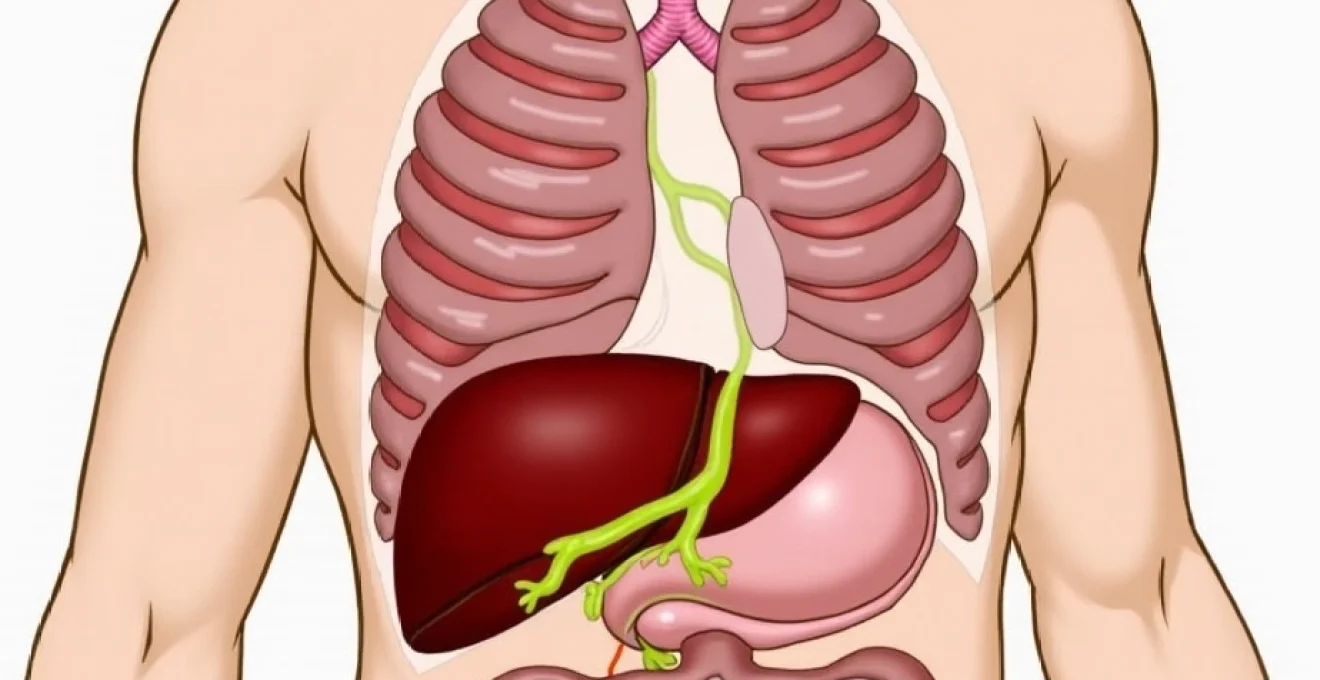

The right rib cage serves as a protective framework for several vital organs that play crucial roles in digestion, metabolism, and overall physiological function. Understanding the anatomical positioning of these organs beneath the right costal margin is essential for healthcare professionals, medical students, and anyone seeking comprehensive knowledge about human anatomy. The right upper quadrant houses a complex arrangement of structures, including the liver, gallbladder, right kidney, portions of the intestinal tract, and parts of the pancreas, each occupying specific anatomical spaces and maintaining important relationships with surrounding tissues.

Hepatic anatomy and right upper quadrant positioning

The liver dominates the right upper quadrant, representing the largest solid organ in the human body and occupying a substantial portion of the space beneath the right rib cage. This remarkable organ weighs approximately 1.5 kilograms in healthy adults and extends from the fifth intercostal space to just below the right costal margin. The hepatic positioning creates a natural protection system, with the ribs shielding this metabolically active tissue from external trauma while allowing sufficient space for the organ’s dynamic functions.

Liver lobar structure and right lobe dominance

The right lobe of the liver comprises approximately 60% of the organ’s total mass and extends significantly beneath the right rib cage. This anatomical dominance means that most hepatic pathology affecting the right upper quadrant originates from right lobe dysfunction or disease. The right lobe’s substantial size and positioning make it particularly susceptible to certain conditions, including hepatomegaly, which can cause noticeable expansion beneath the costal margin and result in palpable masses during physical examination.

Hepatic flexure anatomical relationship

The hepatic flexure represents the junction between the ascending and transverse colon, positioned directly beneath the liver’s inferior surface. This anatomical relationship creates potential for referred pain patterns when either structure becomes inflamed or distended. The close proximity of the hepatic flexure to the liver also explains why certain gastrointestinal conditions can mimic hepatic pathology, making differential diagnosis challenging in clinical practice.

Diaphragmatic surface contact points

The liver’s superior surface maintains intimate contact with the diaphragm, creating the hepatic-diaphragmatic interface that lies directly beneath the right rib cage. This relationship allows for respiratory movement of the liver during breathing cycles, with the organ moving up to 3 centimetres in vertical displacement during deep inspiration. The diaphragmatic attachment also explains why certain liver conditions can cause referred shoulder pain through shared nerve pathways.

Portal triad positioning within hepatic hilum

The portal triad, consisting of the hepatic artery, portal vein, and bile duct, enters the liver at the hepatic hilum, located on the organ’s inferior surface beneath the right rib cage. This critical anatomical region serves as the primary vascular and biliary gateway to the liver, making it a focal point for surgical interventions and a common site for pathological processes that can cause right upper quadrant pain and dysfunction.

Gallbladder fundus location and biliary tree components

The gallbladder occupies a strategic position beneath the right rib cage, nestled within the hepatic fossa on the liver’s inferior surface. This small, pear-shaped organ measures approximately 7-10 centimetres in length and serves as the primary storage reservoir for bile produced by the liver. The gallbladder’s anatomical positioning makes it readily accessible for imaging studies and surgical procedures, while its location beneath the costal margin explains the characteristic pain patterns associated with biliary pathology.

Fundus projection at Mid-Clavicular line

The gallbladder fundus typically projects beyond the liver’s inferior edge at the intersection of the mid-clavicular line and the costal margin. This anatomical landmark serves as a crucial reference point for clinical examination and surgical planning. When the gallbladder becomes distended due to obstruction or inflammation, the fundus may become palpable at this location, creating a positive Murphy’s sign during physical examination. The fundus positioning also makes it the most common site for gallstone impaction and subsequent complications.

Hartmann’s pouch anatomical significance

Hartmann’s pouch represents a small outpouching at the gallbladder neck, positioned just beneath the right rib cage near the hepatocystic triangle. This anatomical feature holds particular clinical significance as it represents the most common site for gallstone impaction, leading to acute cholecystitis and potential complications. The pouch’s location within the protected space beneath the ribs makes surgical access challenging during laparoscopic procedures, requiring careful dissection and identification of critical structures.

Cystic artery and calot’s triangle boundaries

Calot’s triangle, also known as the hepatocystic triangle, lies beneath the right rib cage and contains the cystic artery, which supplies blood to the gallbladder. This small anatomical space, bounded by the cystic artery, common hepatic duct, and liver edge, represents a critical surgical landmark during cholecystectomy procedures. Understanding the triangle’s boundaries and contents is essential for safe gallbladder removal and prevention of iatrogenic injury to surrounding structures.

Common bile duct trajectory through hepatoduodenal ligament

The common bile duct travels through the hepatoduodenal ligament beneath the right rib cage, connecting the biliary tree to the duodenum. This duct’s trajectory places it in close relationship with the portal vein and hepatic artery, forming part of the portal triad. The duct’s position beneath the costal margin makes it susceptible to compression injuries and explains why certain traumatic events affecting the right upper quadrant can result in biliary complications and obstruction.

Right kidney and adrenal gland retroperitoneal positioning

The right kidney occupies a retroperitoneal position beneath the right rib cage, typically extending from the level of the twelfth thoracic vertebra to the third lumbar vertebra. This positioning places the upper portion of the right kidney directly beneath the lower ribs, creating a protected anatomical space that shields the organ from external trauma while allowing for normal physiological function. The kidney’s retroperitoneal location means that pathological processes affecting this organ can cause deep, aching pain that radiates from the costovertebral angle to the lower abdomen and groin.

The right adrenal gland sits atop the right kidney like a small cap, positioned in the superior medial aspect of the renal fossa beneath the right rib cage. This triangular-shaped endocrine gland weighs approximately 4-6 grams and plays a crucial role in hormone production, including cortisol, aldosterone, and catecholamines. The adrenal’s position beneath the ribs provides excellent protection from mechanical injury, though its location can make surgical access challenging when intervention becomes necessary. The gland’s intimate relationship with the kidney and liver creates potential for mass effect when adrenal pathology such as pheochromocytoma or adrenal carcinoma develops.

The renal fascia, also known as Gerota’s fascia, surrounds both the kidney and adrenal gland, creating a distinct anatomical compartment beneath the right rib cage. This fascial envelope serves multiple functions, including organ support, infection containment, and surgical plane definition during retroperitoneal procedures. When pathological processes such as infections or tumours develop within this fascial compartment, they can cause significant distension and pain that manifests as right upper quadrant discomfort and costovertebral angle tenderness.

Ascending colon and hepatic flexure intestinal segments

The ascending colon represents a significant portion of the large intestine positioned beneath the right rib cage, extending from the cecum in the right iliac fossa to the hepatic flexure near the liver’s inferior surface. This intestinal segment measures approximately 15-20 centimetres in length and maintains a retroperitoneal position throughout most of its course. The ascending colon’s location beneath the costal margin makes it susceptible to certain pathological conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, and neoplastic processes that can cause right-sided abdominal pain and altered bowel habits.

The hepatic flexure marks the transition point between the ascending and transverse colon, positioned directly beneath the right rib cage in close proximity to the liver and gallbladder. This anatomical junction represents one of the most acute angles in the entire gastrointestinal tract, creating a natural site for potential obstruction and gas accumulation. The flexure’s position beneath the ribs explains why trapped gas or faecal impaction at this location can cause significant right upper quadrant discomfort that may mimic biliary or hepatic pathology during clinical evaluation.

The relationship between the ascending colon and surrounding retroperitoneal structures creates important clinical implications for diagnosis and treatment of abdominal pathology. When inflammatory conditions affect the ascending colon, the inflammation can spread to adjacent structures beneath the right rib cage, including the right kidney, duodenum, and liver. This anatomical proximity explains why conditions such as Crohn’s disease or colon cancer can present with complex symptom patterns that involve multiple organ systems and require comprehensive diagnostic evaluation to establish accurate diagnoses.

Pancreatic head and duodenal loop anatomical complex

The pancreatic head occupies a crucial position within the duodenal loop beneath the right rib cage, forming an intricate anatomical relationship with surrounding structures. This portion of the pancreas, measuring approximately 6-8 centimetres in diameter, lies posterior to the first part of the duodenum and anterior to the inferior vena cava. The head’s positioning within the right upper quadrant makes it a critical component in the differential diagnosis of right-sided abdominal pain, particularly when pancreatic pathology such as pancreatitis or pancreatic carcinoma develops.

Pancreaticoduodenal arcade vascular supply

The pancreaticoduodenal arcade provides the primary blood supply to both the pancreatic head and duodenal loop, creating a complex vascular network beneath the right rib cage. This arterial system consists of superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries that form anastomotic loops around the pancreatic head. The arcade’s intricate anatomy makes surgical procedures in this region technically challenging and requires careful preservation of blood flow to prevent ischaemic complications. Understanding this vascular arrangement is essential for successful pancreaticoduodenectomy procedures and management of pancreatic trauma.

Ampulla of vater sphincter mechanism

The ampulla of Vater represents the confluence of the common bile duct and main pancreatic duct, located within the medial wall of the second part of the duodenum beneath the right rib cage. This small but critically important structure contains the sphincter of Oddi, which regulates the flow of bile and pancreatic juice into the duodenum. The ampulla’s position makes it susceptible to various pathological processes, including ampullary carcinoma, sphincter dysfunction, and choledocholithiasis, all of which can cause right upper quadrant pain and obstructive jaundice.

Superior mesenteric vessels crossing pattern

The superior mesenteric vessels cross anterior to the pancreatic head and posterior to the duodenal loop, creating important anatomical landmarks beneath the right rib cage. This vascular crossing pattern defines the inferior border of the pancreatic head and serves as a crucial surgical landmark during pancreaticoduodenectomy procedures. The vessels’ position also creates potential for vascular complications when pancreatic pathology develops, including superior mesenteric vein thrombosis and arterial invasion by pancreatic tumours. The crossing pattern’s location beneath the costal margin makes vascular assessment challenging during physical examination, often requiring advanced imaging techniques for proper evaluation.

Right pleural cavity and costophrenic recess boundaries

The right pleural cavity extends beneath the lower right rib cage, creating the costophrenic recess where the parietal pleura reflects from the chest wall to the diaphragm. This anatomical space represents the most dependent portion of the pleural cavity and serves as a collection point for pleural fluid when pathological processes develop. The costophrenic recess’s position beneath the ribs makes it readily accessible for diagnostic and therapeutic thoracentesis procedures, while its location explains why certain pulmonary conditions can cause pain that radiates to the right upper quadrant.

The relationship between the right pleural cavity and subphrenic organs creates important clinical implications for diagnosis and treatment of thoracic and abdominal pathology. When pleural inflammation or infection develops, the inflammatory process can irritate the diaphragm and cause referred pain to the right shoulder and upper abdomen. Conversely, subphrenic infections or abscesses can track upward and involve the pleural space, creating complex clinical presentations that require multidisciplinary management approaches.

The anatomical boundaries of the costophrenic recess extend from approximately the eighth rib posteriorly to the sixth rib anteriorly, creating a significant area of potential space beneath the right rib cage. This extensive boundary explains why pleural effusions can accumulate substantial volumes of fluid before becoming clinically apparent and why complete drainage often requires multiple thoracentesis procedures or chest tube placement. The recess’s anatomy also influences the optimal positioning for thoracic procedures, with the posterior axillary line at the eighth intercostal space representing the safest entry point for most pleural interventions.